- CV Detail -

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

Securing space for public art in crowded urban environments takes political skill, visionary concepts and substantial funding. Starting small might seem like your only option.

Instead, try making art for vast procedural landscapes. There's room for everything in virtual worlds. Disperse your software defined environments right now on the Internet, and maybe someday throughout the cosmos with spacetime independent quantum entanglement.

I had a studio class in 1989 taught by sculptor Stephen De Staebler. Walking across campus he asked about my day job and I told him I designed computer games. He wanted to know what was on the technology horizon and I said virtual reality. I speculated that artists would soon make sculpture unintended for the physical world. With a wry smile, De Staebler replied, "That's a scary thought, Tom."

For my day job in 2000, I was a part-time ironworker at Mark di Suvero's Petaluma, California studio. In the evenings, I designed I‑beam and plate steel sculptures with CAD software by Autodesk, my partner's employer. As a Technical Artist at James Madison University in 2014, I finally experienced this work with Oculus Rift virtual reality headset prototypes.

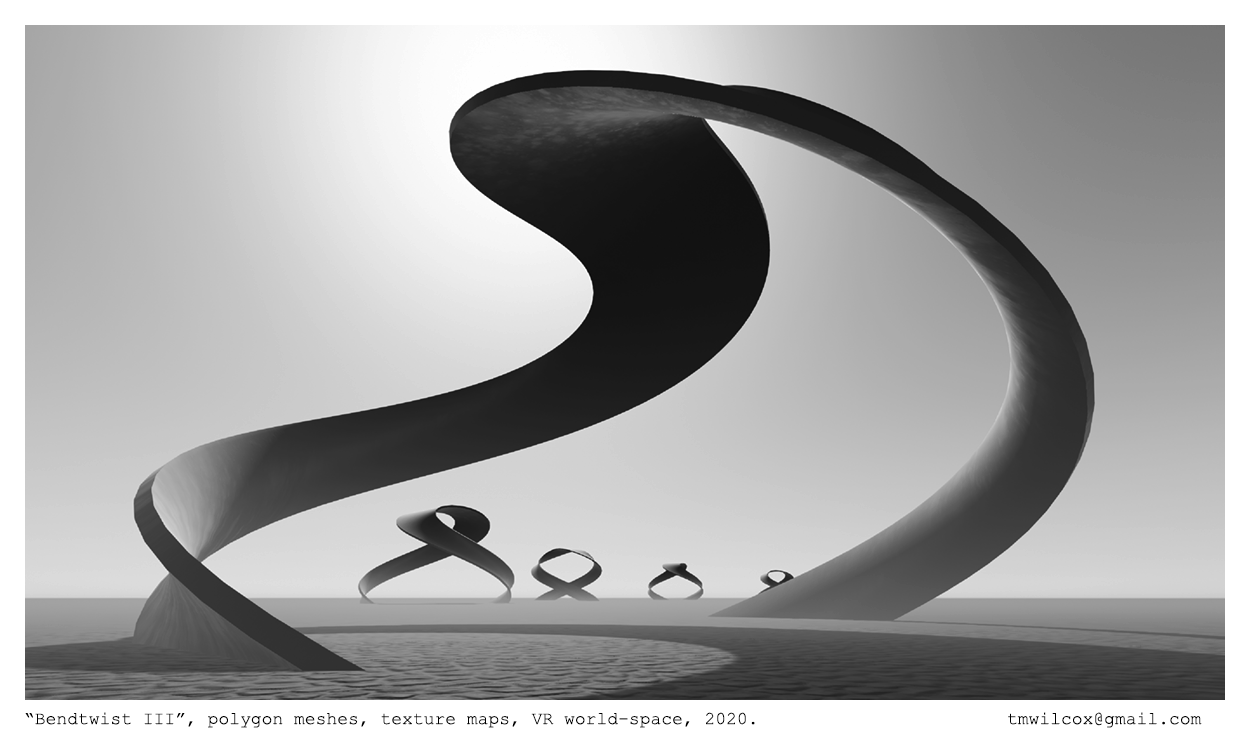

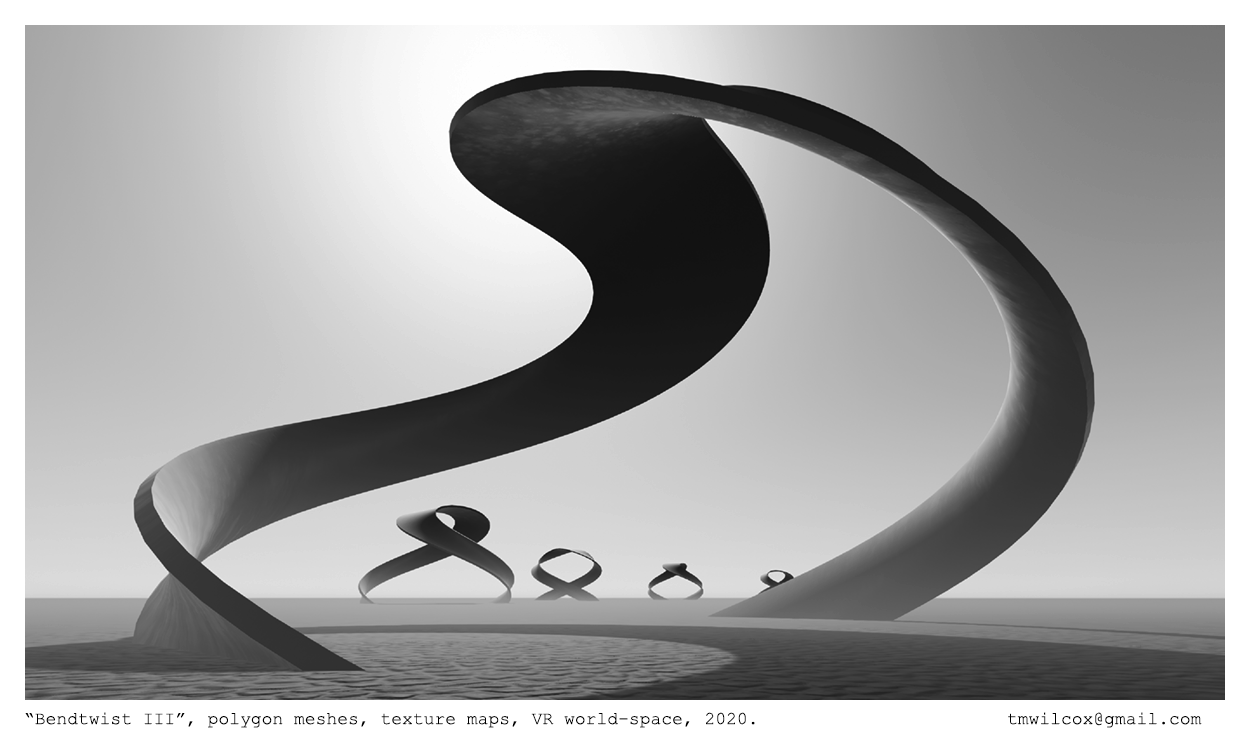

By 2020, I was making polygon mesh objects with 3D scans of handmade maquettes and clay figures, with digital sculpting and surface modeling. Today I design virtual reality user interfaces for navigating procedural landscapes roamed by conversational docents. For my next book, "An Artist In Virtual Worlds", I chronicle the rise of this art form and I imagine its future.

Securing space for public art in crowded urban environments takes political skill, visionary concepts and substantial funding. Starting small might seem like your only option.

Instead, try making art for vast procedural landscapes. There's room for everything in virtual worlds. Disperse your software defined environments right now on the Internet, and maybe someday throughout the cosmos with spacetime independent quantum entanglement.

I had a studio class in 1989 taught by sculptor Stephen De Staebler. Walking across campus he asked about my day job and I told him I designed computer games. He wanted to know what was on the technology horizon and I said virtual reality. I speculated that artists would soon make sculpture unintended for the physical world. With a wry smile, De Staebler replied, "That's a scary thought, Tom."

For my day job in 2000, I was a part-time ironworker at Mark di Suvero's Petaluma, California studio. In the evenings, I designed I‑beam and plate steel sculptures with CAD software by Autodesk, my partner's employer. As a Technical Artist at James Madison University in 2014, I finally experienced this work with Oculus Rift virtual reality headset prototypes.

By 2020, I was making polygon mesh objects with 3D scans of handmade maquettes and clay figures, with digital sculpting and surface modeling. Today I design virtual reality user interfaces for navigating procedural landscapes roamed by conversational docents. For my next book, "An Artist In Virtual Worlds", I chronicle the rise of this art form and I imagine its future.